'The World

at Peace' at Symphony Space

Herb Boyd - special to the New York Amsterdam

News

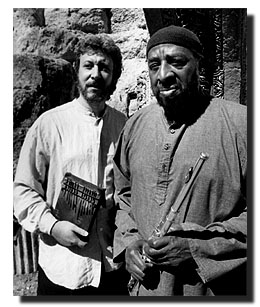

There is no way to know for certain where the

creative genius of Yusef Lateef ends and where Adam Rudolph's begins in

their composition "The World at Peace," which was given its New

York premiere Saturday evening at Symphony Space. Those familiar with their

works might surmise that the languid, expressively Eastern-tinged portions

of the. 100-minute long composition were penned by Lateef and the engagingly

percussive segments can be attributed to Rudolph.

Such speculation, however, is both futile and

pointless since the piece has a seamless flow, a delightful continuity

that invoked a variety of conflicting images from the first movement to

the fourth.

The program notes by the composers provide a

few clues about their intentions. "In composing this piece,"

said Lateef, whose longevity is as ageless as his music, "I explored

avenues I hadn't explored before. A plant living within another plant is

known as an endophyte in biology, and I relate some of these ideas to constructing

melodies and counter-melodies from intervals already existing within a

vertical chord."

When Rudolph says that one of his compositional

tools is "cyclic verticalism" which integrates elements of West

African rhythm, the two composers strike an affinity, and this confluence

of rhythm and sensibility surfaced through the performance. It was particularly

apparent when sections of the ensemble were isolated, in effect, paired

in order to develop harmonic or melodic-intensity.

This method was evident right from the start

with Lateef and Ralph Jones blending their alto flutes in such singular

fashion of density that the notes were extended and deepened at the same

time. Before the concert, trumpeter/flugelhornist Charles Moore indicated

that "Coltrane Remembered," part of the first movement, was related

to "Naima," one of Coltrane's loveliest melodies. "With

the alteration of one note," Moore explained, "Yusef creates

an entirely new and original composition. His music is all about structure

and instrumentation."

Indeed. And a poignant example of this occurred

when Moore's flugelhorn meshed with Jones's bass clarinet and Lateef's

C-flute. Pulsing below this entrancing arrangement was Rudolph's relentless

percussive strokes, and his hands were a blur, faster than hummingbird

wings. After a chorus or two, the propulsive rhythm was in command, and

drummer Hamid Drake and vibist David Johnson pushed the beat to the edge

of chaos.

"I also create a certain aesthetic by assigning

a group of notes to a certain instrument, exclusive of other instruments

which are assigned other groups of notes," Lateef further explains

in his notes. "I derived this idea from Chaos Theory, and the music

that results brings to my mind the music of the Banda, a group of people

from Central Africa." Again, this approach is significant and converges

with Rudolph's polymetric concept and his penchant for drumming styles

and techniques of West Africa.

At the end of the second movement, all of these

notions congeal and reach a powerful crescendo that echoes Coltrane's "Africa

Brass," only here it's a concoction of strings, udu horns, batas and

an electric guitar. The powerful rage gave way to lush serenity after intermission

and the sprigs of beauty blossomed in Marcie Brown's resonant cello, in

Jones's pretty obbligatos on soprano saxophone, in Kenn Cox's pointillistic

forays at the piano, in Johnson's dazzling marimba and most compellingly

in Lateef's haunting flute,

At the core of "The World at Peace"

is a blues sensibility. It is an orchestral redemption song that celebrates

world music, a passionate tone poem about our human drama, our endless

possibilities.

|